Discover more from Good Signal

High Steaks: Health Considerations of Meat vs 'Meat'

“Unlike the cow, we get better at making meat every single day.”

– Pat Brown, Founder of Impossible Foods

When it comes to eating meat, the average person’s diet today looks drastically different from 50 years ago. The second world war and the ensuing post-war period significantly altered diets due to resource constraints, thereby increasing carbohydrate consumption while lowering the intake of expensive fats and meats. After the war ended, food restrictions were relaxed, and meat consumption began its upward trajectory. Although the first report advocating a reduction in meat consumption was released during this period, meat consumption surged in the 1960s with the advent of globalization, which enabled cross-cultural exposure to different cuisines. Red meat consumption peaked in the 1970s until scientists started making the connection between its consumption and cancer.1 As the century came to a close, it was well established that red meat ‘probably’ led to colorectal cancer. Risks related to meat consumption can broadly be classified into three categories – nutrition, disease, and safety. Alternative proteins have emerged as a potential pathway to healthy eating, but to what extent have they been successful?

The Pursuit of Nutrition

Although it provides high protein levels, a variety of nutrients (including iron, zinc, and vitamin B12), and a full complement of amino acids, red meat has come under fire due to its high saturated fat content and LDL cholesterol levels. Processed meat is criticized for its additives and preservatives which lead to high sodium nitrate content, which is considered carcinogenic. In contrast to the flurry of issues associated with red meat, there is no substantial proof of health risks when it comes to poultry or seafood consumption. Certain cuts of chicken such as thighs have higher saturated fat content than others such as chicken breast. Similarly, salmon and mackerel contain higher quantities of healthy fats such as omega-3 but with higher amounts of cholesterol. With poultry and seafood, the baseline risks are significantly lower as compared to red and processed meats. Regardless, with all meat and seafood products, the quantity and quality of the product play a big role in determining the nutritional and safety risks.

Plant-based meat has higher fiber content and lower cholesterol than conventional meat. In addition, combining legumes (such as soy) and cereals (such as wheat) can provide a complete source of protein. Protein derived from microalgal fermentation brings with it the benefit of polyunsaturated fatty acids, a high source of vitamin B12, and great antioxidant concentration.2 Despite these benefits, in its quest of mimicking the texture and taste of conventional meat, it seems nutrition has taken a back seat. Experts have blamed the slow pace of retail uptake of plant-based meats on the long list of ingredients mentioned on plant-based alternatives, along with concerns that these products are ‘hyper-processed’. Other health concerns include high sodium content, the use of bulking agents and additives, and the lack of a complete amino acid profile.

The industry is making strides in addressing these gaps. The evolution of the Impossible Burger from version 1.0 and 2.0 serves as a primary example. The latter boasts 30% lower sodium content and 40% lower saturated fats.3 Several research articles also highlight the differences between the properties of nitrates in animal and plant-based products. That is, sodium nitrate found in processed meats may be carcinogenic, but the nitrate found in whole grains and legumes is beneficial.4 We also see a clean label movement underway which has the potential of improving nutrition and pacifying consumer concerns. Although much of the nutrition data available currently is limited to plant-based proteins, as fermentation and cultivated technologies come online, there will be additional opportunities to bridge nutrition gaps.

The Dread of Disease

Although red meat consumption surfaced in the 1970s, it wasn’t until much later that substantive proof was obtained. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded after a review of 800 studies that processed meat (e.g. sausages, hot dogs, pepperoni, deli meat) could be classified as a Group 1 carcinogen. That is, the evidence was substantial enough to conclude that processed meat can cause cancer. Shortly thereafter, red meat (e.g. beef, mutton, and pork) was classified as a Group 2A carcinogen, indicating that evidence was less straightforward yet substantial enough to conclude that red meat is a probable cause of cancer.5 In this case, studies point specifically to colorectal cancer being more likely than other cancer types. Critically though, the data highlights that the risk of colorectal cancer associated with highly processed meat is approximately twice that of minimally processed red meat. There is also a risk of cardiovascular diseases such as stroke, enlarged heart muscles, hypertension, and ischaemic heart disease. Further, processed meat intake has been associated with a higher risk of type 2 diabetes.6 There is also a risk of nervous system-related diseases such as dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease. Other ailments, like chronic kidney disease, were also found to be positively correlated with higher red meat consumption.

Based on the initial studies conducted on plant-based meat alternatives, they seem to be able to address most of the disease challenges with conventional meat but with varying degrees of efficacy. For example, plant-based meat contains 15% of daily dietary fibre content compared to none in animal meat.7 Research has shown that dietary fibre plays a crucial role in limiting the onset of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colorectal cancer.8 Likewise, another study by the Stanford School of Medicine corroborated the finding that switching conventional meat with plant-based meat reduces various cardiovascular risk factors.9 Finally, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the risk of obesity is heightened by the consumption of food products high in fats and sugars and plant-based meats with lower saturated fats content can be advantageous in managing that risk as well.10 As additional studies further support the health benefits of alternative proteins in combating diseases, they provide strong incentives for consumers to add or substitute plant-based meat in their diets. This is helpful in capturing early adopters and crossing the chasm to reach mainstream customers.

The Road to Safety

An estimated 600 million people in the world fall ill after eating contaminated foods and approximately 420,000 die every year due to food-borne illnesses. Diarrheal diseases are the most common, resulting from the consumption of contaminated food, causing 550 million people to fall ill and 230,000 deaths every year.11 The substantial severity of this risk requires a closer look. Based on data from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there have been 71 known outbreaks of salmonella in the U.S. over a 10-year period from 2012 to 2022. Of these, 33 were linked to meat products, which had the highest susceptibility to these outbreaks.12 Similarly, there have been 33 known outbreaks of e. coli, 12 of which were linked to meat products, with the highest number of cases caused by ground beef.13 A visible example has been the U.S. fast-food chain Chipotle, which has fallen victim to both types of bacterial outbreaks.14 Even after taking precautions and practicing hygiene, the risk cannot be eliminated.

Chemical contamination poses an additional risk with heavy metals such as cadmium, nickel, and lead. The risk of mercury and microplastic contamination in seafood has risen sharply over the past decade due to increasing pollution in water bodies. Seafood is especially susceptible to a high concentration of contaminants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). Chemicals such as PCBs and mercury are known to have health risks related to the brain and the nervous system. This is the reason behind the recommendation that pregnant women limit or abstain from the consumption of seafood (especially raw varieties) as these chemicals can be especially harmful to foetuses. Further, PCBs have also been linked to cancer in humans.15

The use of antibiotics in animal farming is another area of concern as it can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance in humans. A study conducted in Australia found that 57% of the tested meat products resulted in a positive outcome for resistance to at least one antibiotic class.16 Similarly in the U.S., drug-resistant bacteria known as ‘superbugs’ were found on 62% of the tested ground beef samples and 36% of the chicken breast samples.17 There have been multiple laws introduced to limit the antibiotics given to farmed animals 1-3 months before human consumption. However, the fact remains that these rules are not universal, and monitoring and enforcement are challenging. There is also concern related to zoonotic diseases with meat consumption, of which avian influenza and COVID-19 are prime examples. Due to the risk posed by this issue, the U.S. CDC introduced the Antimicrobial Resistance Solutions Initiative to track and improve the ability to respond to ensuing health crises.18

Plant-based alternatives such as seafood are free of mercury contamination and micro-plastics, which is a huge step forward in addressing some of the above concerns. Although eating alternative proteins can address concerns around antibiotic resistance and superbugs, they are still susceptible to bacterial and microbial infections and chemical contamination, as they can carry pathogenic bacteria originating from raw ingredients. Although most of these bacteria typically don’t survive the extrusion process, this is not always the case.19 Another issue focuses on the use of Genetically Modified (GM) ingredients in the production of plant-based meats, particularly the potential accumulation of glyphosate residues in GM soybeans or their associated food products, and the subsequent adverse effects upon ingestion.20 Since fermentation and cultivated meat are at a nascent stage, regulators have formulated novel food frameworks across many geographies to assess their safety. These considerations span testing for residues such as recombinant proteins, viruses, and pathogens. Although cultivated meat may not require genome modification, GMO production methods could be deployed to improve efficiencies which will draw further scrutiny. Given the burgeoning state of the industry, regulators have an opportunity to draft safety regulations from the outset that ensure we are substituting conventional meat with consistent and high-quality products that address existing health risk concerns.

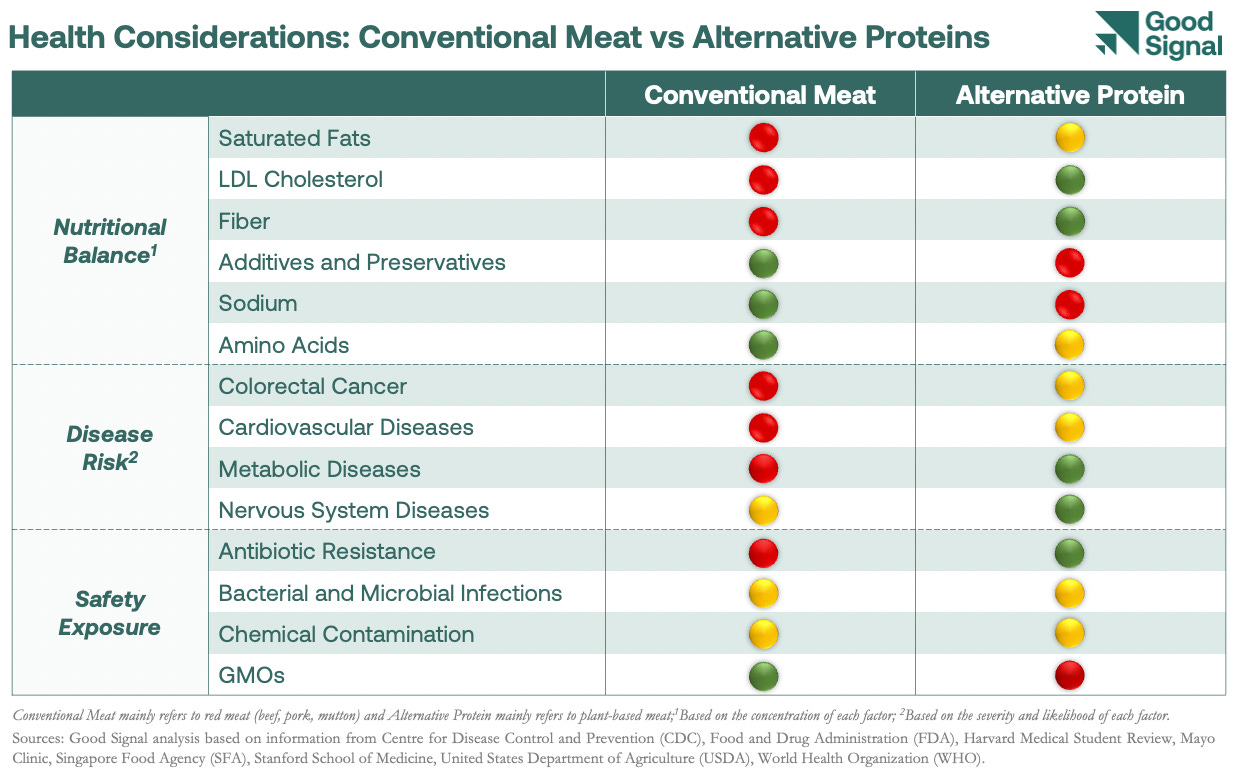

Overall, alternative proteins have positioned themselves as the healthier choice and have made undeniable progress, but have yet to achieve their full potential. The graphic below summarises the health considerations of conventional meat and alternative proteins along the lines of nutritional balance, disease risk, and safety exposure.

The Next Wave

Due to health issues that have come to light with meat consumption, several government organisations have issued public health guidelines and recommendations to reduce meat. For example, the regulatory authorities in the United Kingdom have published guidelines for those who consume more than 90 grams/day of cooked red and processed meat to reduce their intake to 70 grams/day.21 Similarly, the French health authority also recommended limiting red meat consumption to 500 grams/week and charcuterie (processed meat) consumption to 150 grams/week.22 For reference, meat consumption in Europe averages approximately 1,400 grams/week. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) publishes ‘Dietary Guidelines for Americans’. The current 2020-2025 guidelines suggest limiting meat and egg consumption to 740 grams/week.23 As a comparison, in 2018, the average American consumption of meat and eggs was approximately 40% higher than the recommended amounts.24

Health, safety, and nutritional disparities aside, one major difference sets alternative meat apart from its conventional counterpart: it is evolving. With ongoing research in alternative protein offerings, ingredients and processes will improve, and consequently, the industry will offer better products. Research is ongoing as to how ingredients can be better utilized not only to replace negative aspects of meat but also to pack additional nutrients into products. Imagine a new generation of products that not only taste identical to meat but also offer a superior nutritional profile. We may see these offerings not just with cultivated meat but with fermentation and mycoprotein as well. Meat has been around for centuries; alternative proteins are just getting started. Industry upstarts have just produced their first round of products and are back in the lab with consumer feedback in hand to upgrade their offerings. Meat companies have done an amazing job scaling their operations. But at the end of the day, while meat companies are improving their processes, alternative protein companies are improving their products. We’re just getting started with the next chapter of our food system. We expect it to be nothing short of a rollercoaster ride!

Northern Ireland Chest, Heart, and Stroke Organisation

Hadi and Brightwell (2021), Safety of Alternative Proteins: Technological, Environmental and Regulatory Aspects of Cultured Meat, Plant-Based Meat, Insect Protein, and Single-Cell Protein

Plant Proteins Co

Green Queen Media

National Cancer Institute

Giromini and Givens (2022), Benefits and Risks Associated with Meat Consumption during Key Life Processes and in Relation to the Risk of Chronic Diseases

University of Texas

Kaczmarczyz, Miller, and Freund (2012), The health benefits of dietary fiber: beyond the usual suspects of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and colon cancer

Stanford Medicine

IARC Working Group Reports, Number 10 (2017)

WHO

CDC

CDC

Food Poisoning News

California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

McLellan et. al. (2018), Superbugs in the supermarket? Assessing the rate of contamination with third-generation cephalosporin-resistant gram-negative bacteria in fresh Australian pork and chicken

Environmental Working Group (EWG)

CDC

Hadi and Brightwell (2021)

Hadi and Brightwell (2021)

National Health Service (NHS) UK

European Commission Food-based Dietary Guidelines

USDA, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025

USDA, Economic Research Service

Subscribe to Good Signal

Insights on alternative proteins