Discover more from Good Signal

Sell The Sizzle (Not The Steak)

“We don’t buy what we need. We buy the stories we tell ourselves.”

– Seth Godin, Author of ‘This is Marketing’

When it comes to advertising, the meat and dairy industry incumbents have had many decades of experience in optimizing the way they impact consumer purchase decisions. Over the years, they have successfully mastered the art of selling the sizzle instead of the steak and have pulled off some of the most iconic marketing and advertising campaigns in the food industry. Alternative proteins are early in this respect and would benefit from observing and learning from the tactics of the meat and dairy industry.

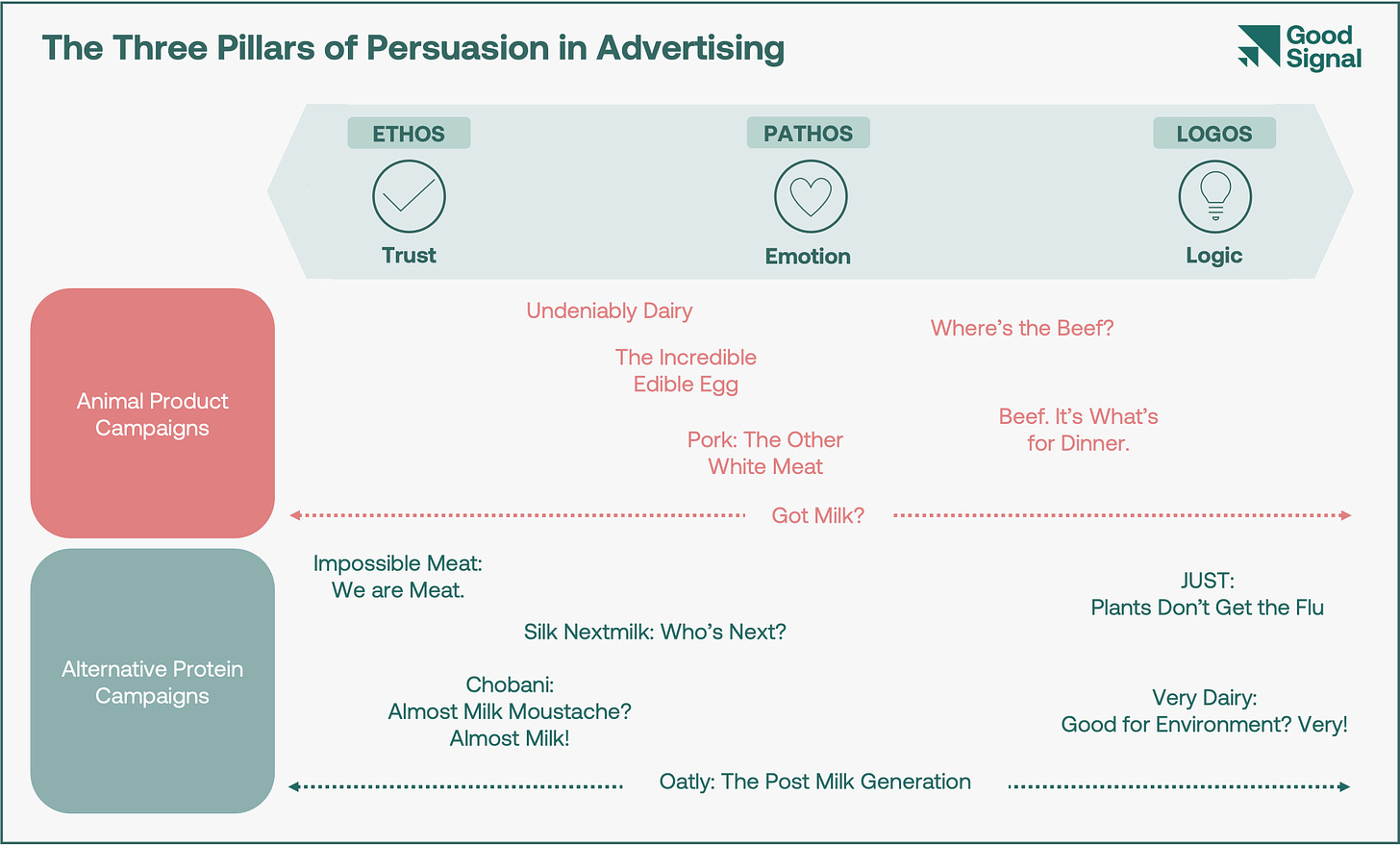

Advertising methodologies have generally undergone a drastic change over the years, from print ads, billboards, and magazines to television, radio, and social media. Despite this shift, the theories that form the building blocks of most advertising campaigns have remained the same. Over 2,300 years ago, Aristotle introduced the ‘Three Pillars of Persuasion’, which outlined the mechanisms through which an author can persuade an audience. The first mechanism, Ethos, focuses on building trust with the reader or audience by establishing authority. The second, Pathos, appeals to the audience’s emotions, while the third, Logos, caters to logic1. Given that the aim of advertising is to take the consumer through the sales process from awareness to consideration, conversion, and finally loyalty, the three pillars are sage advice for developing strategies for consumer persuasion.

The three pillars are effective in influencing consumer decisions because of the way humans think. The dual process theory, made famous through Daniel Kahneman’s book titled Thinking Fast and Slow, explains that humans think in two ways – system 1 and system 2. System 1 refers to the ‘fast’ decisions based on intuition and gut feeling, while system 2 refers to the ‘slow’ decisions based on logic and deep thinking. The two systems work in tandem to combine emotion (system 1) and logic (system 2) to arrive at all decisions2. That being said, research conducted by Harvard Business School professor Gerald Zaltman concluded that approximately 95% of all decisions are subconscious3. Marketing and advertising, especially in the digital age, are all about influencing those subconscious purchase decisions that we make while walking through the grocery store aisles or scrolling through an e-commerce website or app.

People Buy Stories, Not Products

Some of the most memorable taglines for animal product campaigns include Got Milk?, Where’s the Beef?, Pork: The Other White Meat, Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner., and The Incredible, Edible Egg. A key characteristic these campaigns share is that they are run by the checkoff programs in their respective industry segment. Checkoff programs, formally called research and promotion programs, were introduced in 1930 and participation in these programs was initially optional — the farmers ‘checked off’ the box of the program that they wanted to contribute to. In recent times, they have become mandatory in the U.S. and are regulated by the Agricultural Marketing Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). While this process works well for the meat and dairy industries, it does raise questions about the systemic paradox of the policies. The USDA regulates the checkoff programs and ensures that all fees are paid, but it is also the government organisation that releases the U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

The intent of a checkoff program is to promote the product category as a whole without any reference to individual brands. Lately, a checkoff fee is automatically deducted from the producers – almost like a tax4. For example, the beef checkoff requires all producers selling cattle or calves to pay US$ 1 per head through the Beef Promotion and Research Act5. These funds are then funnelled into marketing campaigns. Overall, the beef, poultry, dairy, lamb, and eggs national checkoff programs collectively spent approximately US$ 350 million on promoting their products in 20216. This amount represents 7% of all funding funnelled into alternative proteins in the same year across all technology stacks – plant-based, fermentation, and cultivated.

Got Milk? was an iconic campaign introduced initially by the National Milk Processor Education Program in 1993 and it featured video format ads of people running out of milk at unfortunate moments. Shortly thereafter, the California Milk Processor Board launched its own print ad campaign of famous celebrities proudly displaying milk moustaches with the tagline ‘Got Milk?’. Eventually, the two joined forces7 and the campaign ran till 2014 with 350 print ads and 70 video ads8. The previous tagline, ‘Milk does a body good’, was considered boring and ineffective as consumers were already well aware of the nutritional benefits of milk such as a high concentration of calcium. Retail sales of milk products had declined by 20% over the two decades leading up to 1994. The Got Milk? campaign managed to revive the milk industry and in 1994, retail sales of milk products increased for the first time in almost a decade from 740 million gallons in 1993 to 755 million gallons in 1994. A couple of years later, a research study found that the Got Milk? campaign had increased the sales of milk products by 6%9.

The ‘Milk does a body good’ campaign appealed only to the consumer’s logic. Given that 95% of the decisions are subconscious and driven by emotion, we can see why appealing to logic alone would lead to limited success. The Got Milk? campaign worked so well because it combined the three pillars – ethos (trust), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic). The celebrities in these ads engendered trust – these were people that consumers knew, admired, and even revered. The idea of running out of milk invoked fear and the milk moustaches led to a happy response due to the humorous nature of the image. This combination was incredible as research indicates that happiness, sadness, fear/surprise, and disgust/anger are the four main emotions that effectively impact consumer decisions10. Finally, the ads also featured facts such as health benefits and ease of consumption – just grab a glass, pour milk, and drink it for a healthy meal.

Recently, the dairy checkoff (called Dairy Management Inc.) has been successful in harnessing the power of social media and transitioning toward a new era of checkoff ads11. Dairy Management Inc. partnered with Mr. Beast, one of the top five most subscribed content creators on YouTube, to incorporate facts about dairy farms and farmers in a YouTube video. This was part of a social media campaign called Undeniably Dairy which launched in 2017 and targeted the Gen Z population through platforms such as YouTube and TikTok. On TikTok, the campaign included videos on how to make iced coffee, hot chocolate drinks, cheese boards, feta cheese pasta, and butter boards all with the hashtag #ResetWithDairy. The campaign collaborated with numerous content creators on the app to share these videos. It is notable that none of these videos had any mention of the checkoff name nor asked the viewer to purchase anything. Instead, it engaged viewers by sharing a new recipe or cooking hack which then intrigued the viewer to try it out for themselves. The content also evoked a sense of FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) to entice viewers to try out the recipes and hacks for themselves because everyone else was doing the same. The videos were also peppered with facts about the health benefits of dairy and a few even referred to the improvements in the environmental impact of dairy production (Mr. Beast’s video states that ‘a glass of milk is made with 20% fewer emissions than it was 15 years ago’). This appeals to logic. Finally, these videos are posted by well-known social media content creators (the blue check mark next to their name indicates that they are ‘verified’ and have a substantial following on the platform), generating both credibility and trust. It is notable that both the research and the promotion of its outcome were funded by the checkoff program. A performance review of this campaign highlighted that it led to 72 million video views across all platforms, and as a bonus, a 6% decline in the purchase intent for dairy alternatives, specifically plant-based milk12.

In the meat industry, the ‘Where’s the Beef’ campaign captured the imagination during its time. While it was not run specifically to promote beef, the mention of beef in the tagline makes it relevant to examine. It was introduced by the popular fast food chain Wendy’s to convince its audience that their beef burger patties were thicker and bigger than those of their competitors. The campaign included videos of people opening up burgers with big buns and small patties and looking around asking ‘Where’s the Beef?’. The ad invoked an emotional response from viewers in the form of outrage at the minuscule size of the patties. Since Wendy’s patties were bigger, the logical response expected from the viewers would be to shift to Wendy’s.

Similarly, the ‘Beef. It’s What’s For Dinner.’ campaign utilised simple single-line sentences to entice the consumer to experience the taste of beef. It is reported to have increased beef sales by 26% to 36% and the targeted ad reached approximately one billion people in 201913. The ‘Pork: The Other White Meat’ campaign was launched three decades earlier in 1987 and utilised emotion-evoking taglines such as ‘give your mouth something to smile about’ and ‘invite your tastebuds to dance’, along with relevant images of people smiling and dancing while eating pork. In 2000, research indicated that it was the fifth most memorable tagline of all time. This was a US$ 7 million campaign that resulted in a 20% increase in pork purchases by 199114.

Alternative protein marketing has seen some bright spots. Oatly, the industry’s most visible plant-based milk company, has successfully rolled out a multi-platform marketing campaign. Oatly utilises a string of provocative, guerrilla-style advertising campaigns with taglines such as ‘milk, but made for humans’ and the ‘post-milk generation’ to create a bold, fearless personality around the brand15. On Twitter, Oatly uses the technique of breaking the fourth wall and addressing the consumer directly instead of indirectly talking about the product or the brand. Oatly has also introduced a page titled ‘Hey Barista’ on social media sites where they interview and share the profiles of baristas around the world who vouch for the Oatly product. The company also creatively uses its product packaging to indicate the product’s health and environmental benefits while sticking to its fearless personality to call out the animal dairy industry and its environmental impact. Overall, this unique brand personality appeals to pathos, sharing the barista profiles appeal to ethos and the health and environmental benefits appeal to logos – the full package!

We can deduce that the common cause behind the success of all these campaigns is the simultaneous utilisation of all three pillars of persuasion. Meat and dairy companies have figured out how to sell the sizzle instead of the steak. They focus on the story around the product and on how the product makes the consumer feel instead of focusing on the physical attributes or benefits of the product. For example, the Egg Checkoff spent US$ 10 million in 2021 on developing the ‘Egg story’16. The impact is clear: focusing on the sizzle sells more steaks!

Got Alternative Ads?

Given the strength and deep-rooted entrenchment of incumbents in the industry, advertising for alternative proteins becomes that much harder. The lack of a checkoff system in the alternative protein sector requires that marketing is based on individual brands rather than product categories. The first wave of advertisements from prominent alternative protein companies has seen mixed responses from consumers. Since these campaigns are new, there are no statistics available about their success. However, we can indirectly infer the success through the market share that has been captured. The alternative dairy category has seen the most success and has captured 8% of the global dairy market17. In the U.S., plant-based milk has a penetration of 16%, while meat has garnered just 1.4% market share18.

Prominent advertising campaigns in the sector include the ‘We Are Meat’ campaign by Impossible Meat introduced in 2021. The ads depict images of an Impossible burger sizzling on a hot pan and looking as juicy as a beef patty, signalling that the Impossible patty has all the characteristics of beef. The intended message is clear: Impossible burgers are meat!19 While the ad may have addressed the sizzle instead of the steak (quite literally) and established trust by proving that Impossible is meat, we must ask, what kind of story does the ad tell? What does it make the viewer feel? Similarly, the latest ad by JUST, the leading plant-based egg brand, states that ‘Plants don’t get the flu’. This is an extremely relevant statement given the recent spread of avian flu in the U.S. which has caused the prices of eggs to skyrocket all around the world. The ad is very successful in appealing to logic and proving that JUST's egg substitutes are the safer and better choice. Despite the logical benefits, what kind of imagery does the ad invoke? This is relevant because research has shown that the depiction of images instead of words helps create subconscious linkages which then assist in making instant and intuitive decisions20.

Conventional dairy companies such as Chobani and Danone have also advertised their new plant-based dairy products. Chobani’s ads introduced a new twist to the successful Got Milk? campaign by showing that oat milk can give you almost the same moustache that animal milk gives you. The tagline of ‘Almost Milk’ along with the milk moustache invokes a sense of nostalgia. In the same stride, the dairy giant Danone recently unveiled print ads for their plant-based milk brand called Silk Nextmilk. The ads feature the children of famous celebrities who had taken part in the Got Milk? campaign and depict the children holding a glass of plant-based milk and showing off their plant-based milk moustaches21. This is a terrific attempt at targeting the Gen Z demographic through the children and also the Millennial/Gen X demographic who get nostalgic through the familiar Got Milk? campaign reference. In a previous article, we addressed the plant-based industry’s way of attempting to replicate animal products instead of creating differentiated products. The piggy-backing approach of alternative protein product ad campaigns raises similar questions as well.

Finally, the latest round of ads released by Very Dairy (Perfect Day’s precision fermentation-based milk brand) indicates that animal-free milk is good for health, better for the family, and better for the environment — a flow of thought that is relevant and logical. However, when you’re walking down the milk aisle in the grocery store, will you remember the product that is better for your health and the environment or the product that your favourite celebrity used in their ‘Iced Coffee Hack’ video?

Facts or Feelings (Or Both)

Below is a summary of the characteristics of the various advertising strategies implemented for promoting animal products and alternative proteins along with the pillars used in each ad to persuade the consumer.

While animal product advertising strategies are aimed at increasing the sales of the entire product category, alternative protein companies focus on creating a brand identity and promoting a single product to the consumer. Current strategies have done an admirable job of spreading awareness for these products and their benefits. But to reach mainstream consumers, the industry must both organize itself and evolve its tactics. To do so, it must learn from what the meat and dairy industry has done so well: build a meaningful connection with the consumer that goes deeper than logic.

The alternative protein industry has utilised ethos and logos to capture consumers who make conscious and logical purchase decisions based on what’s good for their health, the environment, and the animals. However, based on the latest research from Boston Consulting Group (BCG), this segment only represents about 20% of all potential customers. The purchase decisions of an additional 20% of consumers are difficult to change. The remaining 60% of the market represents mainstream consumers22. For them to consider a new product over one they have purchased for years, the story around the new product, the messaging of the brand, and the expected product experience have to be far superior. Plant-based dairy is further along in this journey, and its market share reflects it — the segment saw a 12% increase in retail sales from 2021 to 2022. On the other hand, plant-based meat suffered a slight decline in retail sales. While it is impossible to infer a cause-and-effect relationship, it is relevant to consider what has been effective in the plant-based dairy segment and the learnings for the alternative protein industry.

To move forward, we must look back (to both Aristotle and the success of the conventional meat and dairy industries) and formulate a strategy that spans trust, emotion, and logic. Meat and dairy industry incumbents have been using the emotion associated with the sizzle to sell the steak for decades now. The alternative protein industry has developed an improved steak and has been selling it better than ever before. It’s time to take a step further and focus on the sizzle.

The Decision Lab

The Decision Lab

Harvard Business Review

The National Agricultural Law Centre

The Beef Board

Based on Good Signal’s research by compiling the budget allocated for marketing and promotion activities in the 2021 annual statements of the abovementioned checkoffs

The Ana Educational Foundation

The New York Times

Saveur

Boldthink Creative

Sentient Media

Edelman

The Beef Board

The Pork Checkoff

Awario

The Egg Checkoff

Boston Consulting Group (BCG), Taking Alternative Proteins Mainstream

The Good Food Institute (GFI)

Impossible Foods

The Medical Xpress

Green Queen

BCG, Taking Alternative Proteins Mainstream

Subscribe to Good Signal

Insights on alternative proteins